Can You Work in Aerospace in The United States as a Foreign National?

Yes, but there are hurdles 🥇🚧🏃♂️

When I meet with aspiring aerospace engineers (who happened to not be born in the United States) they always ask me how they can get involved with the US aerospace industry. If that’s you, I expect that this article will be of use to you. If that’s not you, you’ll still be amazed to hear about the hurdles foreign nationals (FNs) jump over to get aerospace gigs stateside.

In this article, I’ll touch on some objective considerations for FNs and reference my own personal experience: in 2021, I boarded a plane in Perth (Western Australia) and took a short 25-hour trip to Los Angeles to pursue a career in Aerospace in the US. I studied at the University of Southern California, was a researcher at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), and am now studying at Stanford University. In my time in the US, I’ve met literally hundreds of foreign nationals (FNs) who are doing the same thing I am: trying to break into US aerospace and navigating the associated financial, bureaucratic, immigration, cultural, and personal challenges.

*Note that this article was written in March 2024 and the information included reflects the information available at the time.

The US of A 🌎

So why come to the US in the first place for a career in aerospace? Here are a few common arguments.

The largest aerospace industry on the planet 🏭

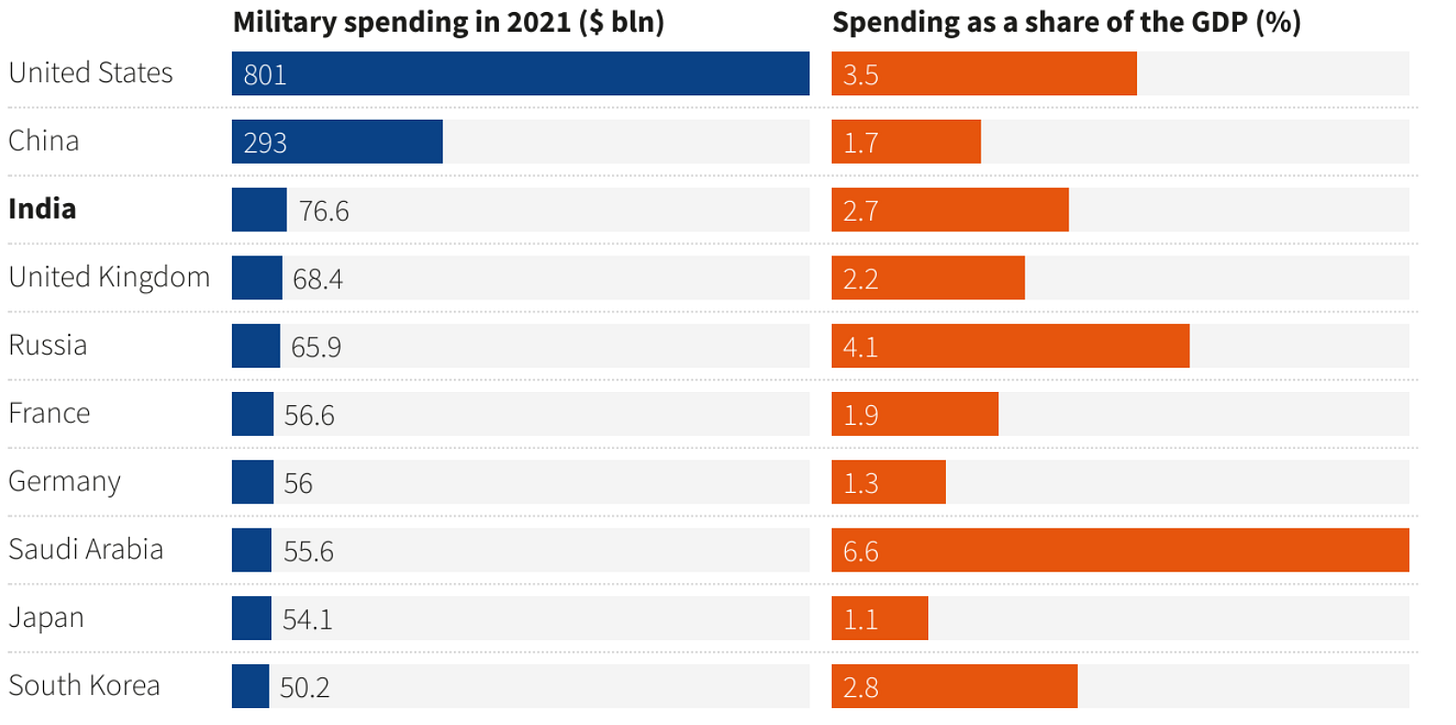

The US aerospace industry is the largest in the world by most metrics. About 500,000 workers are employed in the US aerospace industry, hiring mostly engineers, assemblers/fabricators, and business operations specialists (in that order. The US perpetually leads the highest aerospace exports (100 billion+ USD in 2022) and US aerospace continues to produce the highest level of trade amongst all manufacturing industries. There are no signs of this changing—if anything, US aerospace is becoming more dominant; the emerging private space industry (‘NewSpace’) has a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of around 7-11.2%, and aerospace programs are generally being bolstered by Defense spending that is expected to increase each year until (at least) 2038.

Space heritage 🌑

NASA is one of the earliest government space agencies—being founded in 1958—and has spent the last 66 years ticking all the boxes in terms of demonstrated space capability (people in space, satellites in operation, recoverable payloads, robots on Mars, etc.). Very few countries have this kind of space heritage—that is, a history of doing stuff (well) in aerospace. As mentioned above, the US is also building out impressive capabilities in non-government space organizations (e.g., private industry). I can say anecdotally that in speaking with FNs, this was the number one reason they were pursuing an aerospace career in the US.

Money talks 💵

Money should never be the reason for doing anything, but we all got bills to pay. Depending on the pay differences from your area of specialization and the company hiring you, the US usually lands just behind Switzerland as #2 in terms of the highest paying countries for aerospace engineers (the average annual salary of a mid-level aerospace engineer in the US being approximately ~125,000 USD in 2023). Compare this to my home country (Australia), where you’d comparatively bring in ~110,000 USD on average.

Other considerations 🤔

There are some subjective reasons that might resonate with you too. Note that these don’t (necessarily) represent my personal opinions, but in speaking with FNs, I’ve heard all of these at some point or another:

The weather is good.

The food is good (for some reason whatever the regional burger restaurant is—In-N-Out, Whataburger, Culver's—always becomes the focal point of this argument).

The US is a country that protects personal freedoms more so than the FN’s home country.

The US is a more stable country than the FN’s home country.

The quality of life in the US is improved in some way as compared to in the FN’s home country.

There are bears in California and there aren’t bears in Western Australia and bears are cool animals.

That last one is mine. Before closing out this section, I’ll say that picking a country to call home is a complex decision and the above reasons do not fully encapsulate all considerations. For example; you might make more on paper in the US, but you’ll probably be paying more for healthcare. Similarly, the US aerospace industry being huge doesn’t necessarily mean it’s the best for you.

Beware of acronyms 🔎

If you’re considering if US aerospace is for you, then it’s worth considering EAR and ITAR.

Compliance with regulatory regimes and restrictions 👀

These acronyms stand for Export Administration Regulations and International Traffic in Arms Regulations, respectively. EAR and ITAR pose a challenge to any FN trying to make it in US aerospace, particularly in commercial aerospace and defense-oriented aerospace. They are essentially sets of guidelines, prohibitions, and regulatory regimes that restrict and control the export of goods—particularly military-related technologies—so as to safeguard the US’ national security and economic well-being.

In commercial aerospace in the US you will almost certainly run into EAR restrictions; when an FN deals in technical information that is of commercial interest in the US, it is considered an ‘export’ event. You may well run into ITAR restrictions too; military and defense technology is covered by ITAR, and even technology that may seem innocuous or which does not have a planned military application can fall under ITAR restrictions.

You can read about the exact details more online (EAR, ITAR), but the bottom line is that hiring an FN in a US aerospace company/research institution involves considerably more red tape and ongoing reporting than hiring a US citizen or green card holder (US person). For example, both EAR and ITAR require specific licenses that need to be issued by the Department of Commerce and the Department of State (respectively) which takes time and effort (and thus money) for your employer. This has been discussed in reference to FNs by Federico Rossi at NASA JPL here and by my mate Yuji Takubo here (originally written in Japanese).

You can either jump over these hurdles by:

Finding a manager/boss/employer with a history of working with FNs such that bringing you on board will not require too much extra effort.

Being indispensable to the project, such that your employer has no choice but to work through EAR/ITAR regulations to get you onboard the project.

Or avoid jumping over these hurdles altogether by:

Not working on a project with ITAR/EAR restrictions. Note that research projects (on technologies without specific commercial/military applications) may fall under this category, and some universities in the US conduct this kind of research.

Becoming a US person (e.g. obtaining a green card).

The academic route 🏫

For those looking to study for an advanced degree in the US, you may also want to be on the lookout for the acronyms GRE, IELTS, and TOEFL. A quick rundown:

The Graduate Record Examination is a standardized test that is required by the admissions departments of some graduate-level programs. It assesses your verbal reasoning (reading), quantitative reasoning (mathematics), and analytical writing skills. It can be a real pain to sit and it isn’t cheap—I had to fly to the other side of Australia to find a testing center and pay $300 for the pleasure of sitting the exam. Twice. When applying to schools you should definitely check if these are even necessary; the GRE is being phased out as evidence has come to light that it may decrease diversity and that it does not predict academic success.

The International English Language Testing System is an English language proficiency test, as is the Test of English as a Foreign Language. It assesses your ability to understand English at a university level. I never had to do this but many of my FN colleagues have. Again, it’s a standardized test that can be studied for in a straightforward way: nothing to be scared of, but definitely something to be aware of.

What’s a foreign national to do? 🌏

I naturally can’t speak to every possible pathway or motivation for moving to the US, but I can speak to my own. In reference to the previous sections…

I chose to go to the US for two reasons:

I wanted to pursue an advanced degree in an aerospace-related field. The opportunities available in the US were simply more plentiful than in Australia (at that time).

I wanted to learn about the aerospace industry in a country with greater space heritage than my own. When I was making this decision, the Australian Space Agency (ASA) had recently been founded and ‘building space heritage’ was the phrase on everyone’s lips. What better place to learn about this than the United States?

Furthermore, I elected to enter US aerospace via research that did not have EAR or ITAR restrictions for the simple reason that this seemed easier to me. The rest of my decisions were made for me (I did not have enough personal funding or any financial support from my family to pay for an education in the US). There were only a few scholarships that I was eligible for, and with a lot of luck, I landed a Fulbright Scholarship.

The Fulbright Scholarship 🎓

I want to spend a couple of paragraphs on The Fulbright Program because 1) it’s got a great story, and 2) it’s relevant to virtually all FNs trying to get to the US via a path through advanced study or research. The program came about in 1945 at the end of World War 2: an Arkansas senator named James William Fulbright proposed that the US sell surplus war property to fund an international exchange between the US and other countries, with the goal of lasting peace. He can put it better than I can:

The Fulbright Program's mission is to bring a little more knowledge, a little more reason, and a little more compassion into world affairs and thereby increase the chance that nations will learn at last to live in peace and friendship.

— Senator J. William Fulbright

This program is great for FNs looking to make it into the US via higher education, as there are programs between the US and over 140 countries worldwide. Each country has its own commission with the US, which prescribes the types of scholarships and funding opportunities that are supported. Thousands of grants are awarded annually to folks who are passionate about building bilateral relationships between their home countries and the US. Many of these grants relate to teaching the English language and policy, but the program is increasingly interested in technologies that will shape our collective future (this indeed includes aerospace-related technologies). A common path to success with the Fulbright program is to propose a grant that can only be accomplished in the US (e.g. proposing to investigate aerospace technology at a institution / lab / university with unique expertise or space heritage).

There are of course other relevant scholarships that may be more specific to your country (e.g., the Monash Scholarship in Australia, the Aker Scholarship in Norway, etc.), target university/lab (e.g., there might be funding opportunities specific to say, Caltech), and personal circumstances (e.g., the American Council of the Blind’s Scholarship Program). If you’re interested in seeing a comprehensive list broken down by eligibility criteria, let us know at admin@theoverview.org.

The lengths we go to 😰

It might seem like a great length to go to just to land a space gig but other FNs have done a lot more to take a crack at the US. Here are some quick ones from FNs that I personally know (without naming any names):

A FN from Europe who was using entirely their own savings to fly to Los Angeles, rent an apartment, live in the city, and work at NASA. For context, the only opportunity at that NASA lab available to FNs at the time required FNs to demonstrate that they had independent university funding/scholarship to cover their stay. This student fudged the paperwork to make it look like their own money was university funding, and this 4-month stint personally cost them tens of thousands of dollars.

A FN who became a live-in caretaker for an infirmed man during their time in the US to save on rent.

A FN who was living in a closet during their internship to save money. Like a clothes closet. They couldn’t lie down in it without curling up.

And these are just from people who I personally know—you can find crazier stories online.

Frequently asked questions ⁉️

Before closing, I want to touch on a list of the most frequently asked questions that aspiring aerospace engineers ask me (and my answers):

Will I fit in culturally? This is a very personal question. I moved from Western Australia to California. Culturally speaking, the US and Australia are extremely alike (relative to a global context), and I never really had to worry about the language, the weather, the food, or the way people interact with each other. Your mileage may vary but these are all things you should consider, and there are more comprehensive treatments on this topic available online.

What is the situation in the US politically? Tricky territory here. Without getting political my advice to folks considering the US is to focus on issues that are relevant to them in the states that they are considering moving too. Laws, regulations, and politics vary wildly from state to state in the US and can constantly be in flux; there are some great online tools that provide a starting point for understanding this.

What is the cost of living? Again, this changes dramatically from state to state and between rural and built-up regions. For example, in 2023 the average monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment in California was 1625 USD. In Hawaii it was 1788 USD, in Texas it was 1130 USD, and in Alabama it was 820 USD. These numbers are higher in 2024.

How do I pick a place to work/study? This ultimately comes down to the alignment between your passions in aerospace and the kind of work being done in the US. In speaking with FNs, I’ve heard people approach this with different strategies, narrowing it down by considering 1) what the local NASA facilities focus on, 2) the local space industries, 3) the local labs/institutions/universities, 4) the cost of living, and so on. In general, I will say that my best advice is to focus on the current challenges being tackled by aerospace rather than only considering what you’re interested in at this moment (i.e., favor the ‘industry’s pull’ over the ‘personal push’). For example, there’s a big trend surrounding AI and autonomy in aerospace (at the time of writing), and places that work on those technologies that might not have traditionally been aerospace-focused are becoming more so.

Will you meet with me / read over my application materials / provide feedback? Yep—hit me up at irward@stanford.edu or on LinkedIn.

Parting thoughts 🗭

If you’ve made it this far, you’re obviously considering hopping across the pond to try and make it in US aerospace. I wish you good luck in your decision. I can personally say that the journey is rewarding, that the thrill outweighs the adversity, and that it’s the Wild West out here (in the best way possible).

If you find this article useful or want to give us some feedback, then flick us an email at admin@theoverview.org (if you quote the film Interstellar in your email then Anshuk is contractually obliged to buy you a beer).

Otherwise, keep on rockin’ in the free world 🤠

—IRW