Commercial Aircraft Design: A Brief Introduction

Why do they all look so similar?

“Heavier-than-air flying machines are impossible.”

— Lord Kelvin, 1895

First heavier-than-air flight.

— Wright Brothers, 1903

It would be wrong to say that aircraft are intuitive to design. While flight has long captivated humanity, it took five centuries from the first recorded glider attempts to Leonardo Da Vinci’s sketches and a further five centuries from the sketches to the Wright flyer. Once humans knew they could fly, in just fifty short years, the de Havilland Comet (the first jet airliner) took to the skies, and fifty years later, we have more than 100,000 flights per day. Therefore, in the past century, aerospace engineers have gathered immense information on how to carefully design aircraft that fly safely and reliably, transforming awe into monotony. In this article, I will cover the challenges with aircraft design, provide brief insight into the process, and give you tips on getting started.

Why does pretty much every commercial aircraft look exactly the same?

An aircraft is a highly complex machine that carefully balances weight, safety and cost. Weight is front and foremost. As an aircraft designer, you are in a constant battle with gravity. A heavy aircraft cannot fly, and a light aircraft is too small to carry passengers. A heavy aircraft burns too much fuel, a light aircraft cannot carry fuel. A poorly balanced aircraft flies poorly, and a ginormous aircraft can only land at the longest and strongest runways.

As you sit in the middle seat packed in next to an angry old lady and a mother with a screaming child, eating stale peanuts and drinking flat ginger ale, how close could you be to death? With only three millimeters (eighth of an inch) of aluminum separating you from going 600mph with the top down, it is a testament to the rigor of the aircraft design process that in a given year, you are ten times less likely to experience a fatal aircraft accident than be struck by lightning. In fact, safety is a primary driver of aircraft design. The exacting standards are upheld by the FAA, whose regulations on aircraft design (the FAR 25) determine if your aircraft is allowed to fly at all. So, when you fly, do not be alarmed – aircraft are incredibly overdesigned. In fact, an aircraft structure can withstand almost twice the load it would ever be expected to experience in the most taxing flight conditions. You may notice this is in direct conflict with objective number one: to minimize weight.

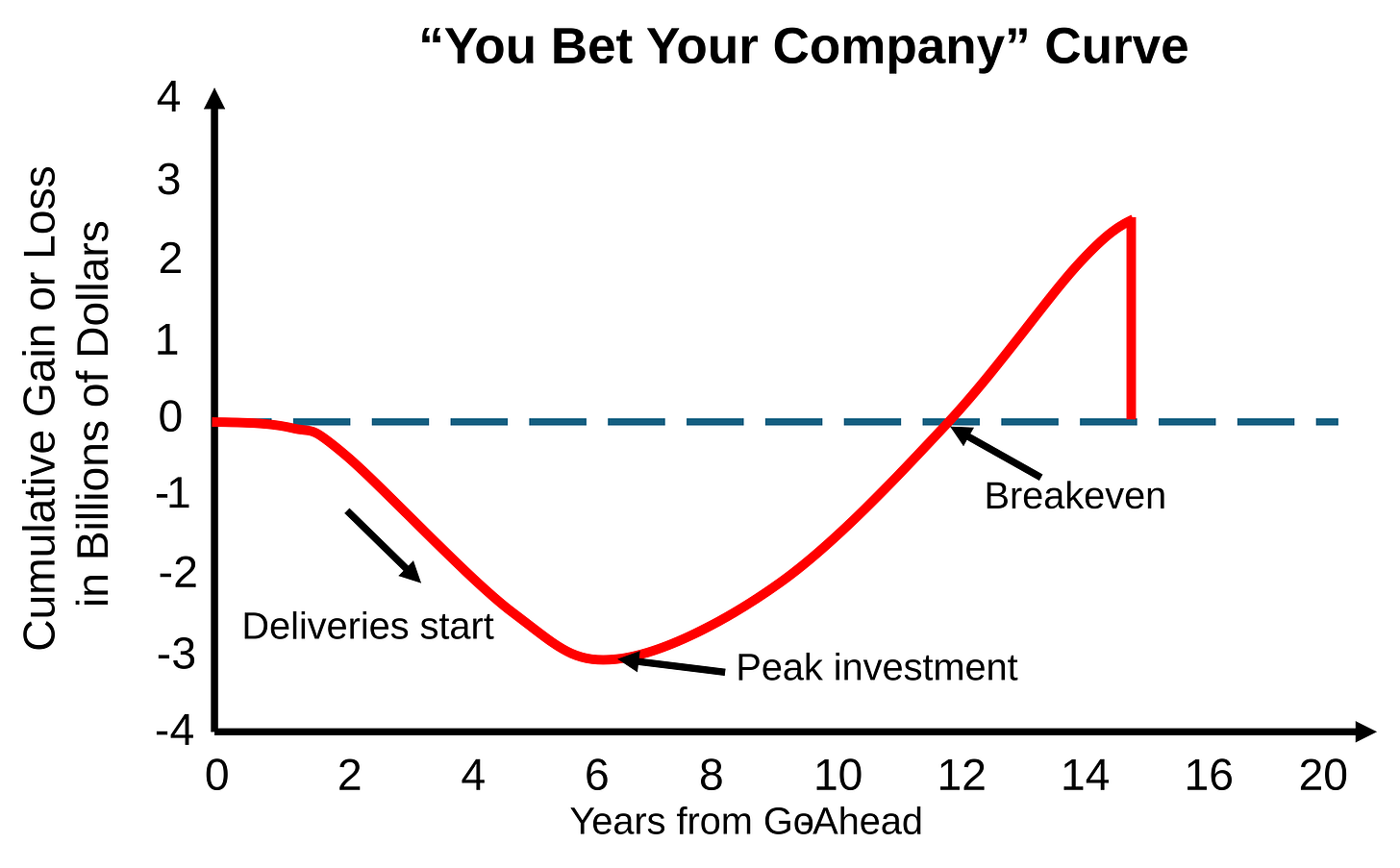

Allow me to touch on one more important factor—cost. The ability to sell an aircraft is paramount: developing a new aircraft is a giant financial risk. The “bet your company” curve below shows just how expensive aircraft programs are and how reliant the manufacturer is on airlines buying their aircraft. You may notice that there is little margin between a profitable and unprofitable aircraft. This is why aircraft manufacturers try to dominate one market segment with one aircraft family (the different variants of an aircraft).

In terms of aircraft design, weight, safety, and cost have potent influences on the design process and the end result. You may have noticed that pretty much every commercial aircraft looks exactly the same. Safety and commercial risk lead to a very conservative design climate, where one relies principally on trusted historical trends and tools, small modifications to existing designs, and large safety margins.

The aircraft design process

Aircraft design is built on iteration. Due to the multitude of competing trade-offs, each aspect of the aircraft, be it aerodynamic, structural, economic among others is progressively refined at each iteration, with information traded between disciplines progressively until the final design is converged upon. The mass-performance sizing loop describes the inter-relation between each discipline in aircraft design and determines what one iteration looks like.

Every aircraft starts with a requirement specification: a list of objectives, such as regulations, noise, airport constraints, fuel burn, etc., that the aircraft must meet. An aircraft’s development lifecycle is based on these iterations.

In the feasibility phase, a conceptual design is produced, where an aircraft’s feasibility is evaluated. This is where the most significant technological developments and the market case must be evaluated.

If an aircraft is determined to be feasible, manufacturable and profitable, the aircraft concept phase begins, which prioritizes getting the design to meet the requirements and selecting key systems architectures and their manufacturers.

By the end of the conceptual phase, the cabin design is well defined, and the overall characteristics of the aircraft, though not perfect, will not change significantly. This is where design-for-manufacture occurs, and the long process of painstaking parts testing happens.

The aircraft enters the final phases, where it is rigorously tested, certified, and determined safe to fly.

More information on Airbus site

Within the design phases, each discipline has its own specific roles and tradeoffs in aircraft design. But they do not exist in isolation – each discipline must inform the overall design and a compromise must be reached that works for every discipline. Systems engineers coordinate and evaluate to produce a cohesive design, mainly using the requirements. To design an aircraft, the weight of the aircraft is calculated by weight engineers to infer the dynamic and static handling qualities. (Is the aircraft stable? Does it buck like a horse?) One must determine the complex structure – the spars, ribs, wing skin, and fuselage – that carries the required loads and withstands the required speeds and maneuvers. One must optimize the aircraft's aerodynamics, determine how the flaps will deploy, and size the wings and tail. Propulsion systems must be designed, integrated, evaluated, and tested for bird strike. The aircraft must address a proven weakness in the market, major airlines must be willing to purchase it, and there must be feasible program and operating costs.

How to study aircraft design

Aircraft design is an excellent introduction to aerospace engineering and an excellent example of engineering thinking, specifically when applied to complex systems. Learning a little about it would be useful to any aspiring engineer.

I have always been fascinated by good design, the kind that is unremarkable until you realize the thought that went into it. However, the challenges of aircraft design have historically limited the opportunities for good design. During my undergrad, I enjoyed designing unconventional aircraft for my class projects, so I got a feel for how to design an aircraft when you are breaking the rules. My research now is on generative machine learning for aircraft design, integrating physics to overcome the issue of being unable to be creative in the conceptual design phase, and giving aircraft design a more "move fast break things" attitude in the initial stages.

If you are interested in aircraft design, there are resources that I heartily recommend.

Read airport planning guides – the guides produced by aircraft manufacturers packed with information on their aircraft for the people who need to operate and design around the aircraft. (Example for the A320)

I would also highly recommend reading the FAR 25 requirements to understand the complexities of the constraints on aircraft designs.

There are also plenty of fantastic textbooks:

A particularly great introduction is Daniel Raymer’s “Conceptual Aircraft Design.”

For a complete treatment, peruse Jan Roskam’s eight-volume masterpiece “Airplane Design.”

To design your own aircraft, look at the examples in “Jane’s All the Worlds Aircraft” for inspiration, and play around with XFLR5/AVL and OpenVSP.

If you’re particularly brave, you may even find yourself 7000 feet removed from the ground in an aircraft of your own (see the picture below).

Happy dreaming!

Aurelien